Myra J Tait, Athabasca University and Natalie Diane Riediger, University of Manitoba

“Sin taxes” are a tried, although not necessarily true, strategy for reducing harm connected to alcohol and tobacco. Calls for a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages are supported by a large body of evidence linking weight gain and Type 2 diabetes, to excess consumption of these drinks. This response is supported by the World Health Organization, among others, to offset negative health and economic effects.

The idea of taxing sugar-sweetened beverages has caught the attention of political leaders in Canada, too. However, this paternalistic “we know best” approach ignores the most obvious needs and rights of Indigenous Peoples. Rather than seeing the harms of colonization to Indigenous Peoples, governments are fixating on how to tax the Coke in their hands.

Imposing a sugary beverage tax on Indigenous consumers would be unethical, contravene tax law and undermine Indigenous rights to self-determination. Even the production of sugar in Canada has exploited Indigenous people, who were used essentially as forced labour.

Health and mental health gaps

The connection between lack of employment, education and family supports, to poorer health outcomes is well documented. For Indigenous peoples, who often occupy the worst end of wellness measures, this is directly connected to the legacy of colonization.

Moreover, the health gap is profound and getting worse. The Manitoba Centre for Health Policy found the life expectancy gap between First Nations persons and all other Manitobans has widened to 11 years from eight years since 2002.

It comes as no surprise then that Indigenous Peoples also experience diabetes at much higher rates. In Canada, treating diabetes costs upwards of $30 billion per year. It seems unlikely that a tax on sugary drinks can set this crisis right.

Similarly, for those struggling with addiction, eating disorders or other challenges, adding more tax provides no support for better “lifestyle choices.” There is evidence linking adverse childhood experiences and trauma to higher intake of sugar-sweetened beverages both in childhood and later in life, as well as calls to include sugar-sweetened drinks within addiction models, including for survivors of childhood maltreatment who disproportionately use food to cope.

Indigenous Peoples are also more likely to live with mental illness and addiction, largely due to intergenerational trauma. This raises ethical questions about taxing addiction or behaviours associated with trauma, particularly in light of its colonial roots.

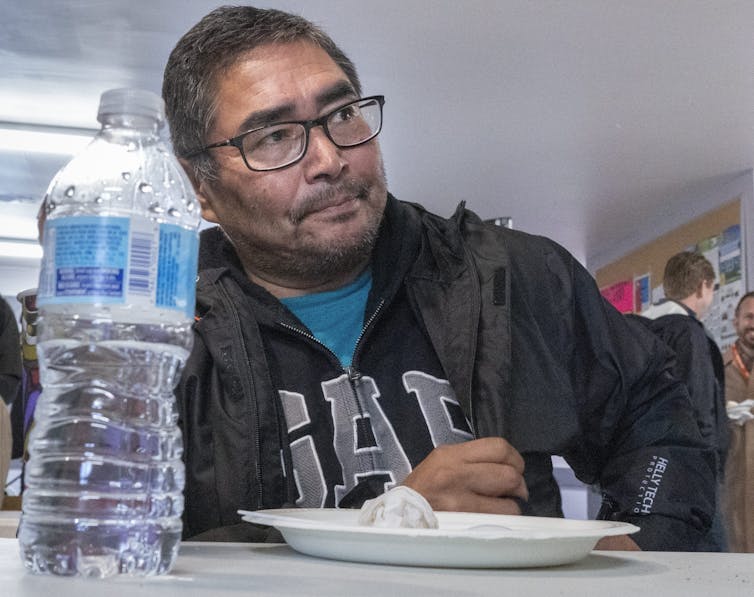

A water bottle sits on the table in front of Chief and NDP candidate Rudy Turtle during a visit by NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh on Oct. 5, 2019 on the Grassy Narrows First Nation, where industrial mercury poisoning in its water system has seriously affected the health of the community. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Paul Chiasson

Taxes, food and water

One obvious problem with taxing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption by First Nations persons is their tax-exempt status for all purchases made on reserves. There is no Canadian tax scheme that can avoid this exemption, thus a tax on sugary beverages has no impact on those who are at highest risk for Type 2 diabetes. With the growing presence of urban reserves in many Canadian cities, buying tax-exempt sugar-sweetened beverages is increasingly easy.

Taxation also doesn’t address underlying issues of food insecurity, prevalent in communities with high Indigenous populations. In urban areas, the 2015 Canadian Community Health Survey found Indigenous populations to have the highest intake of sugar-sweetened beverages of any racial or ethnic group. This often reflects a lack of healthy and affordable food in neighbourhoods with large Indigenous populations.

Canada’s historic approach to resource development and wildlife management has been to ignore the needs and rights of Indigenous communities. Industry was allowed to pollute water bodies, including with mercury, and destroy food sources relied upon by Indigenous Peoples. For northern, rural, remote and urban populations, food insecurity continues to be a problem. Increasing food prices wouldn’t fix this.

A tax on sugar-sweetened beverages implies that Indigenous Peoples can either make better food choices, or choose to pay the tax. Yet safe drinking water and affordable food are not within reach of many Indigenous Peoples.

The disconnect here is how taxing sugary drinks will help reduce diabetes and other health problems for this group. There is a serious credibility gap when governments demand consumers pay extra when choices are limited, and then promise tax revenue will be used to benefit their health. Despite promises by the federal government to fix all boil water advisories in five years, it failed to deliver on this basic human right.

Shifting responsibility

The solution, it seems, shifts responsibility for wellness from addressing inequality, to imposing a sugar-sweetened beverage tax on those most affected by poverty and lack of clean water, and for whom racism in health care is a daily reality. By framing the “problem” just the right way, the “solution” is easy to sell to a nation struggling to accept responsibility for the continuing harms of colonization.

As a young nation, Canada signed Treaty agreements to share land and resources. Instead of honouring those promises, Canada enacted the Indian Act, essentially stripping First Nations of even the most basic human rights. Since then, Canadian governments have rarely acted in the best interests of Indigenous Peoples.

Today, Canada is considering Bill C-15 to adopt minimum standards of Indigenous rights as set out in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. This includes the right to self determination. Rather than taxing sugar-sweetened beverages, a better solution is to end paternalism and to provide real choices by confronting inequality and racism.![]()

Myra J Tait, Assistant Professor, Governance, Law and Management, Athabasca University and Natalie Diane Riediger, Assistant Professor of Nutritional Epidemiology, University of Manitoba

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Featured Image: Laura Green, a resident of Shoal Lake 40 First Nation, was photographed while speaking about water and access issues in her community on Feb. 25, 2015. The boil water advisory at Shoal Lake 40 has lasted more than two decades, beginning in 1997.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/John Woods